100 Years of Deco Glamour, Part 1

All That Jazz

-

Promotional poster for the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, designed by Robert Bonfils (France, 1925)

Photo © V&A Museum

-

David-Weill Desk by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (France, ca. 1918–19)

Photo © Met Museum

-

Printed Silk by Paul Poiret (France, ca. 1919)

Photo © Met Museum

-

Raisins Soufflé Vase by Emile Galle (France, ca. 1920)

Photo © Hickmet

-

Bauhaus Tea Infuser & Strainer by Marianne Brandt (Germany, ca. 1924)

Photo © Met Museum

-

Hotel du Collectionneur at the Exposition des Arts Decoratifs et Industrieles Modernes in Paris, 1925

Photo © SiefkinDR

-

The Swedish National Pavilion designed by architect Carl Bergsten for the 1925 Art Deco expo in Paris

Public domain

-

Lacquered Metal Vase by Jean Dunand (France, ca. 1925)

Photo © Met Museum

-

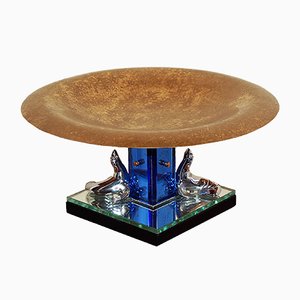

Aufsatz Centerpiece by Josef Hoffmann (Austria, ca. 1925-1931)

Photo © Artnet

-

Suzanne by René Lalique for Lalique et Cie (France, 1925)

Photo © Corning Museum of Glass

-

The salon of the Hotel du Collectioneur, with furniture by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann and painting by Jean Dupas (France, 1925)

Photo © SiefkinDR

-

Fauteuil Transatlantique By Eileen Gray for Galerie Jean Desert (France, 1925-1930)

Photo © V&A Museum

-

Aluminum & Ebonite Lamp by Jacques Le Chevallier (France, ca. 1926-27)

Photo © Met Museum

-

Table Lamp by Poul Henningsen (Denmark, c. 1927)

Photo © Studio Schalling

-

"Skyscraper" Bookcase by Paul T. Frankl (Austria/USA, ca. 1927)

Photo © Sotheby's

-

Weil-Worgelt Study, decorated by the Alavoine decorating firm (France/USA, ca. 1928)

Photo © Brooklyn Museum

-

Silvered Bronze & Onyx Clock by Albert Cheuret (France, ca. 1929)

Photo © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

-

Cedric Gibbon's set design for Our Modern Maiden (USA, 1929)

Photo © MGM

-

Vaso delle Donne delle Architetture by Gio Ponti for Richard Ginori (Italy, 1923-1930)

Photo © Christie's

-

Lady's Desk & Chair by Maurice Dufrène (France, ca. 1930)

Photo © Sotheby's

-

Bergères by Paul Follot (France, ca. 1930)

Photo © Expertissim

-

Smoking Set with Lacquer Tray by Yamakawa Kōji (Japan, 1931)

Photo © The Leveson Collection

-

Interior of Palais de la Porte Dorée, constructed for the 1931 Colonial Exhibition in Paris, with furniture by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann and frescos by Peter Duco

Photo © Palais de la Porte Dorée

-

The Glass Salon, designed for Suzanne Talbot by Paul Ruaud, with furniture by Eileen Gray (France, 1932)

Photo © SiefkinDR

-

Dressing Table by Norman Bel Geddes for Simmons Furniture Company (USA, ca. 1932)

Photo © Met Museum

-

Tea Urn & Tray by Eliel Saarinen (Finland/USA, ca. 1934)

Photo © Cranbrook Museum of Art

-

Dahua Cinema by Yang Tingbao (Nanjing, China, 1934)

Public Domain

-

Goddess Figure by Josef Lorenzl (Austria, ca. 1930s)

Photo © 20th Century Decorative Arts

-

Chairs n Macassar Ebony with Mother of Pearl Inlay by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (France, ca. 1935)

Photo © Master Art

-

PRR S1 Steam Locomotive by Raymond Loewy (USA, 1939)

Photo © US Library of Congress

-

Bentwood Lounge Chairs by Jan Vanek for UP Zavody (Czechoslovakia, ca. 1935)

Photo © Tschechisches Wohndesign

-

Tubular Steel Armchairs from Mücke-Melder (Czechoslovakia, ca. 1930s)

Photo © Tschechisches Wohndesign

-

Sparton Table Radio by Sparks-Withington Co. (USA, ca. 1936)

Photo © Brooklyn Museum

-

Cinema Impero by Mario Messina (Asmara, Eritrea, 1937)

Photo © Sailko

-

Cocktail Set by Norman bel Geddes (USA, 1937)

Photo © Brooklyn Museum

-

Art Deco-style hotels in Miami Beach (USA, ca 1930s-40s)

Photo © Alexf

-

Loveseat by Osvaldo Borsani for Atelier di Varedo (Italy, 1942-1944)

Photo © Jochum Rodgers

-

Custom-Made Dressing Table by Osvaldo Borsani for his family home, Villa Borsani (Italy, 1939-1945)

Photo © Bea de Giacomo for L'AB/Pamono

Don't throw the past away / You might need it some rainy day /

Dreams can come true again / When ev'ry thing old is new again

—Peter Allen, “Everything Old is New Again,” as featured in All That Jazz (1979) and The Boy from Oz (1998)

Everything that’s old is new again. The adage holds true in fashion, music, theater, and beyond, and the design world is no exception. The latest resurgence? A truly fab Art Deco renaissance. Of late, we’ve witnessed an unmistakable revival of the Art Deco aesthetic titillating and inspiring several of today’s most exciting designers, from beloved established names like India Mahdavi to rising stars like Cristina Celestino, Hagit Pincovici, and Anthony Bianco.

As a term, Art Deco is pretty imprecise, and yet we all seem to know it when we see it. How can that be? Although the style lacks a strict, unchanging definition, the unabashed glamour of Art Deco objects and interiors remains instantly recognizable. And while the blossoming of the Deco aesthetic can be traced to one glorious moment in 1925 Paris, it’s made regular cameo appearances again and again in our design culture ever since.

Technically, the Art Deco style arose in France between the first and second world wars. It wasn’t called Art Deco back then, however, but rather Style Moderne. And it wasn’t ever really confined to designers from France. The principal figures associated with the movement, who may or may not have considered themselves a part of it, generally favored luxe materials, geometric motifs, and masterful artisanal craftsmanship. But then again, many others embraced the technological advances of their day and designed in decidedly modest, machine-made materials like tubular steel and molded plywood. To add to the confusion, the Art Deco epithet is familiarly applied to design work that originated in the postwar era too—and continues to be used to describe contemporary design. Mon dieu!

In this three-part series, Pamono will take you on a stroll through the last 100 years and consider how and why Deco has become one of the most enduring styles of the 20th and, thus far, 21st centuries. So let’s start at the beginning—just after the turn of the century.

Haute Deco

Style Moderne was already prevalent in France in the 1910s, but the critical moment when the world took notice was the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs Industriels et Modernes in Paris. Organized by La Societe des Artistes Decorateurs with the mission of restoring French decorative arts to their former glory, this citywide event showcased the work of both French and international artisans, architects, and designers who competed to demonstrate the superior elegance and sophistication of their decorative chops over all others. Notable names that emerged victorious: furniture designers Jacques Adnet, Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann, and Maurice Dufrène; architects Josef Hoffmann, Victor Horta, and Eliel Saarinen; glass designers René Lalique and Émile Gallé; and fashion designers Erté and Paul Poiret.

With so many international participants vying to unite their own idiosyncratic regional heritages with cross-cultural au courant tastes, it’s not surprising then that such a wild range of aesthetic expressions coalesced under the Deco moniker. Sources of inspiration included art movements like Constructivism, Cubism, Futurism, and Surrealism, alongside “exotic” vernacular motifs drawn from the Middle East, Asia, and Africa. Still others built on the foundations of Art Nouveau, a turn-of-the-century, pan-European design movement that also celebrated traditional craftsmanship while favoring ornamentation that invoked the natural world.

Modern-Cum-Deco

The Deco Exposition took place just as the modernist movement was kicking off, as a group of design visionaries and theorists began to venerate the machine, eschew handmade production processes, and reduce design forms to their bare minimum. Although the Exposition is remembered most as a showcase for opulent furniture and décor—like zebra-skin-upholstered settees and inlaid ivory commodes—it also hosted a handful of architect-designers who were on a mission to eliminate unnecessary ornamentation altogether in order to place functionalist concerns at the forefront. Le Corbusier’s contribution to the Exposition, the landmark Pavilion de l’Esprit Nouveau, served as a direct protest against Art Deco’s gratuitously lavish tendencies and offered up the purist aesthetic that would define modernist design for years to come. Rather ironically the proto-modern tubular steel and bentwood furniture designs of the 1920s and ’30s have come to be seen as Deco-esque, due more to the coincidence of time rather than any shared conceptual underpinnings. Another irony is that Le Corbusier is sometimes credited with coining the term Art Deco after he published a series of critical articles about the exhibition, titled 1925 Expo: Arts Déco.

International Deco Iterations

Through the 1930s and ’40s, the Deco flair found followers around the world, from the Americas to Eastern Europe, and onward to Australia and Japan. One notable example hailing from Czechoslovakia is Jindřich Halabala, whose enchantingly curvy furniture is currently experiencing a renaissance among vintage lovers. Likewise the early work of Italian architect-designer Osvaldo Borsani, who—before he launched the modernist manufacturing company Tecno in the 1950s—created bespoke plush and decorative furnishings for his father’s company Arredamenti Borsani Varedo. And few Deco designers are in higher demand today than Irish designer Eileen Gray. Her dramatic Dragon’s Armchair (1917-9) sold at Christie’s in 2009 at a record £19.4 million, making it the most expensive piece of 20th-century design to ever be auctioned.

Deco Architectural Facades

Inspired by the sensational pavilions of the 1925 Expo and the graphically charged motifs found throughout, Art Deco began to find expression in the architecture of many major cities around the world, including Melbourne, Miami, Havana, Rio de Janeiro, and Montevideo. London’s Underground is home to numerous examples of Art Deco architecture, as well as many of the city’s hotels, such as the Strand Palace Hotel. Shanghai boasts over fifty Art Deco buildings, the majority of which were designed by Hungarian architect Laszlo Hudec, and Indonesia has the largest remaining collections of 1920s Art Deco buildings in the world. Of course for the most iconic examples of Art Deco architecture, look to the skyline of New York City. The Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and Radio City Music Hall are incredible achievements of Art Deco, pairing classical symmetry with machine inspired imagery. The facades and motifs of Deco architecture would in turn find a way back into later versions of Art Deco furniture and décor.

America's Streamline Moderne

During the mid-to-late 1930s, a new interpretation of Art Deco developed in America, often called Streamline Moderne or Streamline Deco. This brash, optimistic style formed a visual counterbalance to the austere economic times in which it arose, and all manner of design objects, from furniture and lighting to vacuum cleaners and radios, began to echo the dynamic forms of the newly established travel industry: think lavish ocean liners, mass-produced automobiles, powerful locomotives, futuristic airplanes, and imposing zeppelins. Within the material limitations of the Great Depression, America’s first generation of celebrity designers—Walter Dorwin Teague, Raymond Loewy, Norman Bel Geddes, and the like—popularized this stripped down but still sleek version of Art Deco using more affordable materials like metal, glass, ceramic, and cement. And Hollywood set design of the era ensured the Deco look remained firmly associated with glamour and opulence.

Because the Art Deco story doesn’t stop here, check out Part II, which picks up on the Deco revivial in the 1960s, and Part III, which examines the current trend for Deco inspiration in contemporary design.

-

Text by

-

Rachel Miller

Rachel is a California native whose passion for travel has led her on some pretty crazy adventures around the world. After living in Korea for three years, she decided on a whim to move to Germany. While she still has a wandering soul, Berlin has captured her heart, and she's decided to make this multicultural hub her permanent home. Most of her free time is spent playing beach volleyball, exploring the city's many arty scenes, and hunting down Berlin's best craft beer.

-

More to Love

Art Deco Chandelier by Nics Frères & Degué

Vintage Leather Suitcase from Louis Vuitton, 1930s

Vintage Lacquered Cabinet by René Drouet

Art Déco Bonbon Jar from Robj

Bauhaus Lamp by Marianne Brandt, 1930s

Large Art Deco Table Lamp by Jacques Adnet, 1930s

Art Deco Bronze & Tinted Glass Centerpiece from Buschi, 1930s

Italian Art Deco Sideboard with Gold Leaf, 1930s

Czech Art Deco Coffee and Dessert Service from Epiag

Night Stand Lamps by Christian Dell for Kaiser Idell, 1930s, Set of 2

Chauffeuse by Jean-Maurice Rothschild with tapestry upholstery by Emile Gaudissart, commissioned for the Grand Salon of the S.S. Normandie ocean liner (France, ca. 1934)

Photo © Écomusée de Saint-Nazaire / Jean-Claude Lemée; courtesy of Cité de l'Architecture et du Patrimoine

Chauffeuse by Jean-Maurice Rothschild with tapestry upholstery by Emile Gaudissart, commissioned for the Grand Salon of the S.S. Normandie ocean liner (France, ca. 1934)

Photo © Écomusée de Saint-Nazaire / Jean-Claude Lemée; courtesy of Cité de l'Architecture et du Patrimoine

The interior of l'Esprit Nouveau, designed by Le Corbusier & Pierre Jeanneret for the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (France, 1925)

Photo © Les Arts Décoratifs / éditions Albert Lévy

The interior of l'Esprit Nouveau, designed by Le Corbusier & Pierre Jeanneret for the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (France, 1925)

Photo © Les Arts Décoratifs / éditions Albert Lévy

H-269 Chair by Jindrich Halabala for UP Závody Brno (Czechoslovakia, ca. 1930s)

Photo © Davint Design, sro.

H-269 Chair by Jindrich Halabala for UP Závody Brno (Czechoslovakia, ca. 1930s)

Photo © Davint Design, sro.

The Chrysler Building, designed by architect William Van Alen for Walter P. Chrysler (USA, 1928-1930)

Photo © Postdlf

The Chrysler Building, designed by architect William Van Alen for Walter P. Chrysler (USA, 1928-1930)

Photo © Postdlf

Designer Raymond Loewy photographed amid some of his designs (USA, ca. 1934)

Photo © US Library of Congress

Designer Raymond Loewy photographed amid some of his designs (USA, ca. 1934)

Photo © US Library of Congress